The T. rex Debate:

Fast or Slow, Hunter or Scavenger?

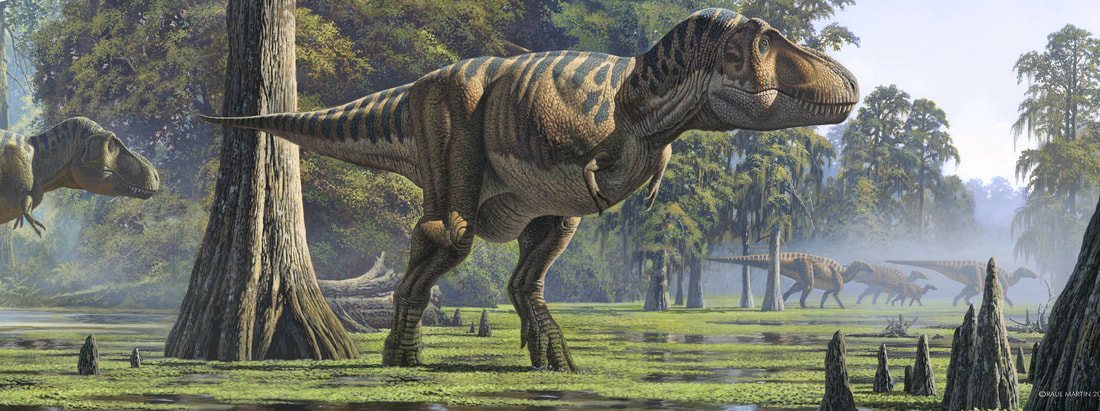

In Jurassic Park, T. rex is seen chasing a Jeep. The dinosaur is able to keep up with the vehicle until it gets up to about 40 miles per hour. Would this have been possible? The movie also showed T. rex jumping out of some trees, chasing down a Gallimimus and making a meal of the animal after a gruesome attack.

One of the hot topics among paleontologists the last couple of years has been whether or not T. rex was able to run fast and whether is was a hunter or a scavenger. On one side of the argument are scientists who believe that T. rex was a swift hunter, capable of running as fast as 40 miles per hour (60 km per hour). On the other side of the argument are scientists who believe T. rex was not able to move at much more than a walk and had to scavenge already dead carcasses to feed itself. It is not just the speed of this famous dinosaur that comes into question; how fast it could move would have determined a great deal about its behavior.

In order to find out more about this debate, and possibly come up with some answers, the Jurassic Park Institute spoke with a number of prominent paleontologists.

Dr. Jack Horner, who was a consultant on all three Jurassic Park films, has caused quite a stir among his fellow paleontologists by insisting that T. rex was a slow moving dinosaur that lived primarily by eating the already dead carcasses of dinosaurs and other animals. He believes that it was only rarely that T. rex would have been able to kill something. Dr. Horner believes that the leg bones of T. rex are designed to prevent it from running or even walking very quickly.

Recent research from Stanford University states that the reason T. rex could not run quickly is because it did not have enough muscle mass in its legs and hips to get it moving much faster than a jog. However, a jog for an animal the size of T. rex could be as fast as a cantering horse or a charging rhino.

The majority of scientists seem to feel that T. rex was not a scavenger, that it could move quickly for an animal of its size, that it was an active and very effective predator and killer. The best way to figure out how all these different conclusions have been arrived at is to look at the evidence being examined by the scientists.

T. rex is very well known from a number of fossil skeletons, a couple of which are nearly complete. Peter and Neal Larson, along with their staff at the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research have discovered the two most complete fossils of T. rex; a specimen they named Stan, which is about 42 feet long, and the very famous fossil known as Sue which is close to 44 feet long. Both of these fossils had more than 90% of their bones found, making it very easy to determine what they looked like. In addition to these specimens, at least 20 other T. rex individuals have been found, although none as complete as Stan and Sue. Recent discoveries of smaller, juvenile T. rex specimens have been able to shed some light on the growth process of these great beasts.

The most striking feature about T. rex is its head. This huge head, the product of millions of years of predatory dinosaur evolution, has been described as the perfect killing machine. This head is one of the first arguments used against the scavenger T. rex theory. The head can be up to 5 feet long, its mouth is filled with 60 teeth that are not only sharp, but thick enough to crunch through armor and bone, and it has eyes set far apart and facing forward. This eye arrangement would have allowed T. rex to judge distances accurately, a feature found almost exclusively in predatory animals.

The teeth of a T. rex are the end result of more than 150 million years of evolution. From the Triassic, through the Jurassic, and for most of the Cretaceous, predatory dinosaurs had teeth that were fairly thin, curved slightly backwards and had very sharp, serrated cutting edges. These teeth were perfect for slicing through skin and muscle, but would not have been very useful for biting into a bone. Up until the time of T. rex, most predatory dinosaurs had long arms and large hands with sharp claws that could be used as weapons as well as for grabbing and holding prey. The direct ancestors of the T. rex, one of which was Albertosaurus, began to develop smaller arms. They made up for this lack of arm power by having larger, stronger heads with teeth that were thicker and able to withstand biting into bone.

When T. rex finally appeared, near the end of the age of the dinosaurs, it had a huge head and small arms relative to its size. Each arm was about the size of a large human arm, but it was much more muscular. A T. rex could probably have lifted 500 pounds (225 kilos) with each arm – hardly a puny, worthless appendage. The hands of T. rex had only two fingers, basically a thumb and forefinger. The claws on these hands were several inches long and could have been used for grasping an animal very closely to its body.

The legs of T. rex were long and strong. By studying muscle attachments on the fossil bones, scientists can tell how large the muscles would have been. Looking at other parts of the fossils tells scientists where skin and muscle were attached so they can figure out its shape and come close to knowing its weight.

All the things described above are accepted by just about all the scientists. It is how they interpret this information that causes them to debate with one another over behavior.

Scavenger or Hunter

Dr. Horner has taken a stance that has become very unpopular among dinosaur fans and many scientists. He states that T. rex was a scavenger, relying on the kills of predatory dinosaurs to find its food, or waiting to find an animal that died of naturals causes or an accident. His reasoning for this is based on several features of T. rex which he feels would have prevented it from being an active hunter:

1.Small arms – Dr. Horner feels that the arms of T. rex were too small to be of any use during a fight and if the animal fell or was knocked over, it would have been unable to use its arms to break its fall, causing it to break the bones in its body.

2.Thick teeth – The teeth of T. rex are not designed to slice flesh as are those in other predatory dinosaurs, says Dr. Horner. These type of teeth would be more useful for getting what is left after smaller predatory dinosaurs had made the kill. He argues that the bones and sinewy flesh would be what remains on a carcass after the killers have eaten their fill and that the bone-crushing ability of T. rex would come in handy to finish off the remains.

3.Slow legs – Dr. Horner points out that the upper leg bone, or femur, is longer than the lower leg bone, or tibia, on a T. rex. He states that on predatory dinosaurs the opposite is true and that the arrangement that is on T. rex would have made it unable to move quickly enough to hunt.

4.Brain parts – The fossilized brain case of T. rex seems to show that the area of its brain devoted to vision is very small and the area devoted to its sense of smell is quite large. Dr. Horner believes that if T. rex were a hunter it would need better vision so that it could see its prey and judge the distance for an attack. He points out that the way its brain is made is similar to that of a vulture, a scavenger that can smell a dead carcass from as far as 25 miles (40 km) away. A well developed sense of smell is more important for a scavenger than a predator, argues Dr. Horner.

5.Evidence of predation – Dr. Horner says that there is no fossil evidence that T. rex was a hunter/killer, only that it was a scavenger. He bases this on the fact that fossil bones of other dinosaurs that bear the tooth marks of T. rex are on bones that would not have been bitten during an attack or a kill, but only after the animal has died. He suggests that a healed T. rex bite would show it was a predator, but that no such evidence exists.

Dr. Horner is in a small minority in his belief that T. rex was a scavenger. Following is the evidence cited by scientists who disagree with Dr. Horner and show that T. rex was an active hunter.

1.Small arms – No one disagrees with the fact that T. rex has small arms for its overall body size. Several scientists point out that there are many predators that do not use arms in hunting and killing. These include birds such as eagles and larger animals such as crocodiles. If a large animal such as T. rex fell, there is definitely a good chance it would break a bone or hurt itself in the fall, especially if it had no way to break its fall using its arms. The fact is, there are almost no fossils of T. rex that don’t show a number of injuries, most attributed to fighting. This is even true of other large predatory dinosaurs that had longer arms. The Allosaurus known as Big Al showed no fewer than 12 serious (and healed) injuries. It has also been suggested that the arms of T. rex could have been used to help lift the animal off the ground if it was lying down to sleep or rest, but some scientists who have closely studied T. rex. believe it could never have used its short arms to do that.

2.Thick teeth – While it is true that T. rex had thicker teeth than any other large theropod, it also had the most powerful bite. The muscles used to close its mouth were huge and would have enabled it to drive its teeth into flesh and bone. The teeth of T. rex had a long row of serrations on the front and back edges, just like other predatory dinosaurs which would have helped it both in a killing bite and slicing the flesh once its prey was dead. Having thick teeth would have had other advantages; they would have been harder to break, and since its teeth would have been its main weapon having broken teeth would have been a big problem. The combination of thick, sharp teeth and a head full of muscles powerful enough to drive them through flesh and bone would have made for a very effective hunter.

3.Slow legs – The question is, how fast does a T. rex need to go? This animal had very long legs, about 11 feet (3.5 m) long on a full grown adult. Some scientists have said T. rex could go as fast as 42 miles per hour (60 kph) which is really fast. A recent study done at Stanford University, which focused on how much muscle a T. rex needs to move that fast, concluded that the top speed for an adult T. rex would have been about 25 mph (40 kph.) That is still as fast as many horses can canter and as fast as a charging rhino. Is that fast enough to keep a T. rex in dinosaur dinner? Paleontologist Ron Stebler made an interesting point. He said that the fossils of T. rex are found in an area of North America that was mostly covered in pine tree forests during the Cretaceous. A forest environment would prohibit both predator and prey from going anywhere too quickly – they would be running into trees! Having great speed would have been a waste, so evolution would not have developed this in a large predator. In a forest, most predators are ambush hunters, hiding behind trees and using a short burst of speed to pounce on passing prey. As far as the physics of the muscles that were the focus of the Stanford University study, Neal Larson said that, when scientists studied the biomechanics of a bumblebee, they proved it couldn’t fly. Neal pointed out that modern crocodiles are capable of running much faster than humans. He also pointed out that none of the scientists conclusions are based on studies of the best T. rex skeletons available. The Stanford University study focused primarily on one T. rex specimen with regard to judging proportions, but the co-leader of the study pointed out that he had examined many of the existing T. rex remains prior to this study and determined that the specimen used for the study was representative of all adult T. rex specimens.

4.Brain parts – The general opinion about the make-up of the T. rex brain is that it had good vision and a great sense of smell, which would have made it effective in both finding and attacking food. A well developed sense of smell would not have made it a poor hunter. Its visual sense was not reduced by having the ability to smell prey or a carcass from a great distance.

5.Evidence of predation – The idea that there are no healed T. rex bites brought a few chuckles from some of our paleontologists. No one seemed to feel that if a T. rex was able to bite another animal that there would have been any chance to survive and heal. There are dozens of fossils that show bite marks that seem to clearly show an attack bite by a T. rex. At least three T. rex skeletons, eight different Triceratops skeletons and a hadrosaur pelvis with a large part of its left hip area missing, are all evidence of T. rex attacks and not scavenging. The hadrosaur bite is on top of the hip of a dinosaur that was about 18 feet (5.5 m) long and would have stood about 8 feet (2.5 m) tall. The only large predator that could have made a kill like that was T. rex. It is unlikely that any dinosaur would have been sitting still to allow a slow-moving T. rex to come over and bite it. In this case, it appears that T. rex would have been chasing the poor duckbill and bit down on it from above; certainly not something a scavenger would have done. It has been estimated that the bite of a large T. rex would have ripped as much as 500 pounds (225 kilos) of flesh and bone from its unfortunate prey.

Did T. rex ever scavenge for its food? The answer is that it definitely did – all top predators, such as lions and tigers, will eat something that is already dead. One theory put forward about T. rex is that as it got really big and heavy, it would have been able to scavenge more. Its huge size and ferociousness would have enabled it to chase off other predators who had made a kill and take it for itself. This had the advantage of T. rex not needing to expend the energy of chasing down prey, as moving five tons of dinosaur during a chase would have used up a lot of its energy reserves. Another fact that supports this idea is that a younger T. rex was proportionally lighter, and therefore faster and more agile. It wasn’t until they got up over 30 feet (10 m) long that they began to get really bulky and heavy.

Dr. Thomas Holtz, co-author of the Jurassic Park Institute Dinosaur Field Guide, has done a great deal of research on T. rex. He has looked at all of the evidence that has been presented by both sides of the arguments. Dr. Holtz cautions against accepting any of the opinions or conclusions as absolute fact. “Tyrannosaurs as a group (of dinosaurs) have locomotion (fast movement) related adaptations; long legs, shock absorbing feet and very large hip muscles,” he said. “T. rex was a better and faster mover than any other large predatory dinosaur and better designed for speed than large living animals like elephants.” He agreed with the possibility that a 3,000 pound juvenile T. rex may have been considerably faster that a six ton adult. Dr. Holtz said that T. rex went through several growth stages and as it grew the proportions of its body changed. “A young T. rex has the same body type as an ostrich-like (ornithomimid) dinosaur, much more athletic than a full sized adult T. rex.,” he said. “A young T. rex may have been able to run flat out, where a large adult may have been unable to run at top speed.”

The disagreements about T. rex behavior will probably go on for some time. It is not likely that any evidence will be discovered that will answer all the questions and leave no room for further discussion. Without a time machine that would give us a look at a living T. rex, we must continue to look at fossil evidence, however sparse and uncertain it may be.

Originally published as T. rex: What was it really? in 2002

One of the hot topics among paleontologists the last couple of years has been whether or not T. rex was able to run fast and whether is was a hunter or a scavenger. On one side of the argument are scientists who believe that T. rex was a swift hunter, capable of running as fast as 40 miles per hour (60 km per hour). On the other side of the argument are scientists who believe T. rex was not able to move at much more than a walk and had to scavenge already dead carcasses to feed itself. It is not just the speed of this famous dinosaur that comes into question; how fast it could move would have determined a great deal about its behavior.

In order to find out more about this debate, and possibly come up with some answers, the Jurassic Park Institute spoke with a number of prominent paleontologists.

Dr. Jack Horner, who was a consultant on all three Jurassic Park films, has caused quite a stir among his fellow paleontologists by insisting that T. rex was a slow moving dinosaur that lived primarily by eating the already dead carcasses of dinosaurs and other animals. He believes that it was only rarely that T. rex would have been able to kill something. Dr. Horner believes that the leg bones of T. rex are designed to prevent it from running or even walking very quickly.

Recent research from Stanford University states that the reason T. rex could not run quickly is because it did not have enough muscle mass in its legs and hips to get it moving much faster than a jog. However, a jog for an animal the size of T. rex could be as fast as a cantering horse or a charging rhino.

The majority of scientists seem to feel that T. rex was not a scavenger, that it could move quickly for an animal of its size, that it was an active and very effective predator and killer. The best way to figure out how all these different conclusions have been arrived at is to look at the evidence being examined by the scientists.

T. rex is very well known from a number of fossil skeletons, a couple of which are nearly complete. Peter and Neal Larson, along with their staff at the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research have discovered the two most complete fossils of T. rex; a specimen they named Stan, which is about 42 feet long, and the very famous fossil known as Sue which is close to 44 feet long. Both of these fossils had more than 90% of their bones found, making it very easy to determine what they looked like. In addition to these specimens, at least 20 other T. rex individuals have been found, although none as complete as Stan and Sue. Recent discoveries of smaller, juvenile T. rex specimens have been able to shed some light on the growth process of these great beasts.

The most striking feature about T. rex is its head. This huge head, the product of millions of years of predatory dinosaur evolution, has been described as the perfect killing machine. This head is one of the first arguments used against the scavenger T. rex theory. The head can be up to 5 feet long, its mouth is filled with 60 teeth that are not only sharp, but thick enough to crunch through armor and bone, and it has eyes set far apart and facing forward. This eye arrangement would have allowed T. rex to judge distances accurately, a feature found almost exclusively in predatory animals.

The teeth of a T. rex are the end result of more than 150 million years of evolution. From the Triassic, through the Jurassic, and for most of the Cretaceous, predatory dinosaurs had teeth that were fairly thin, curved slightly backwards and had very sharp, serrated cutting edges. These teeth were perfect for slicing through skin and muscle, but would not have been very useful for biting into a bone. Up until the time of T. rex, most predatory dinosaurs had long arms and large hands with sharp claws that could be used as weapons as well as for grabbing and holding prey. The direct ancestors of the T. rex, one of which was Albertosaurus, began to develop smaller arms. They made up for this lack of arm power by having larger, stronger heads with teeth that were thicker and able to withstand biting into bone.

When T. rex finally appeared, near the end of the age of the dinosaurs, it had a huge head and small arms relative to its size. Each arm was about the size of a large human arm, but it was much more muscular. A T. rex could probably have lifted 500 pounds (225 kilos) with each arm – hardly a puny, worthless appendage. The hands of T. rex had only two fingers, basically a thumb and forefinger. The claws on these hands were several inches long and could have been used for grasping an animal very closely to its body.

The legs of T. rex were long and strong. By studying muscle attachments on the fossil bones, scientists can tell how large the muscles would have been. Looking at other parts of the fossils tells scientists where skin and muscle were attached so they can figure out its shape and come close to knowing its weight.

All the things described above are accepted by just about all the scientists. It is how they interpret this information that causes them to debate with one another over behavior.

Scavenger or Hunter

Dr. Horner has taken a stance that has become very unpopular among dinosaur fans and many scientists. He states that T. rex was a scavenger, relying on the kills of predatory dinosaurs to find its food, or waiting to find an animal that died of naturals causes or an accident. His reasoning for this is based on several features of T. rex which he feels would have prevented it from being an active hunter:

1.Small arms – Dr. Horner feels that the arms of T. rex were too small to be of any use during a fight and if the animal fell or was knocked over, it would have been unable to use its arms to break its fall, causing it to break the bones in its body.

2.Thick teeth – The teeth of T. rex are not designed to slice flesh as are those in other predatory dinosaurs, says Dr. Horner. These type of teeth would be more useful for getting what is left after smaller predatory dinosaurs had made the kill. He argues that the bones and sinewy flesh would be what remains on a carcass after the killers have eaten their fill and that the bone-crushing ability of T. rex would come in handy to finish off the remains.

3.Slow legs – Dr. Horner points out that the upper leg bone, or femur, is longer than the lower leg bone, or tibia, on a T. rex. He states that on predatory dinosaurs the opposite is true and that the arrangement that is on T. rex would have made it unable to move quickly enough to hunt.

4.Brain parts – The fossilized brain case of T. rex seems to show that the area of its brain devoted to vision is very small and the area devoted to its sense of smell is quite large. Dr. Horner believes that if T. rex were a hunter it would need better vision so that it could see its prey and judge the distance for an attack. He points out that the way its brain is made is similar to that of a vulture, a scavenger that can smell a dead carcass from as far as 25 miles (40 km) away. A well developed sense of smell is more important for a scavenger than a predator, argues Dr. Horner.

5.Evidence of predation – Dr. Horner says that there is no fossil evidence that T. rex was a hunter/killer, only that it was a scavenger. He bases this on the fact that fossil bones of other dinosaurs that bear the tooth marks of T. rex are on bones that would not have been bitten during an attack or a kill, but only after the animal has died. He suggests that a healed T. rex bite would show it was a predator, but that no such evidence exists.

Dr. Horner is in a small minority in his belief that T. rex was a scavenger. Following is the evidence cited by scientists who disagree with Dr. Horner and show that T. rex was an active hunter.

1.Small arms – No one disagrees with the fact that T. rex has small arms for its overall body size. Several scientists point out that there are many predators that do not use arms in hunting and killing. These include birds such as eagles and larger animals such as crocodiles. If a large animal such as T. rex fell, there is definitely a good chance it would break a bone or hurt itself in the fall, especially if it had no way to break its fall using its arms. The fact is, there are almost no fossils of T. rex that don’t show a number of injuries, most attributed to fighting. This is even true of other large predatory dinosaurs that had longer arms. The Allosaurus known as Big Al showed no fewer than 12 serious (and healed) injuries. It has also been suggested that the arms of T. rex could have been used to help lift the animal off the ground if it was lying down to sleep or rest, but some scientists who have closely studied T. rex. believe it could never have used its short arms to do that.

2.Thick teeth – While it is true that T. rex had thicker teeth than any other large theropod, it also had the most powerful bite. The muscles used to close its mouth were huge and would have enabled it to drive its teeth into flesh and bone. The teeth of T. rex had a long row of serrations on the front and back edges, just like other predatory dinosaurs which would have helped it both in a killing bite and slicing the flesh once its prey was dead. Having thick teeth would have had other advantages; they would have been harder to break, and since its teeth would have been its main weapon having broken teeth would have been a big problem. The combination of thick, sharp teeth and a head full of muscles powerful enough to drive them through flesh and bone would have made for a very effective hunter.

3.Slow legs – The question is, how fast does a T. rex need to go? This animal had very long legs, about 11 feet (3.5 m) long on a full grown adult. Some scientists have said T. rex could go as fast as 42 miles per hour (60 kph) which is really fast. A recent study done at Stanford University, which focused on how much muscle a T. rex needs to move that fast, concluded that the top speed for an adult T. rex would have been about 25 mph (40 kph.) That is still as fast as many horses can canter and as fast as a charging rhino. Is that fast enough to keep a T. rex in dinosaur dinner? Paleontologist Ron Stebler made an interesting point. He said that the fossils of T. rex are found in an area of North America that was mostly covered in pine tree forests during the Cretaceous. A forest environment would prohibit both predator and prey from going anywhere too quickly – they would be running into trees! Having great speed would have been a waste, so evolution would not have developed this in a large predator. In a forest, most predators are ambush hunters, hiding behind trees and using a short burst of speed to pounce on passing prey. As far as the physics of the muscles that were the focus of the Stanford University study, Neal Larson said that, when scientists studied the biomechanics of a bumblebee, they proved it couldn’t fly. Neal pointed out that modern crocodiles are capable of running much faster than humans. He also pointed out that none of the scientists conclusions are based on studies of the best T. rex skeletons available. The Stanford University study focused primarily on one T. rex specimen with regard to judging proportions, but the co-leader of the study pointed out that he had examined many of the existing T. rex remains prior to this study and determined that the specimen used for the study was representative of all adult T. rex specimens.

4.Brain parts – The general opinion about the make-up of the T. rex brain is that it had good vision and a great sense of smell, which would have made it effective in both finding and attacking food. A well developed sense of smell would not have made it a poor hunter. Its visual sense was not reduced by having the ability to smell prey or a carcass from a great distance.

5.Evidence of predation – The idea that there are no healed T. rex bites brought a few chuckles from some of our paleontologists. No one seemed to feel that if a T. rex was able to bite another animal that there would have been any chance to survive and heal. There are dozens of fossils that show bite marks that seem to clearly show an attack bite by a T. rex. At least three T. rex skeletons, eight different Triceratops skeletons and a hadrosaur pelvis with a large part of its left hip area missing, are all evidence of T. rex attacks and not scavenging. The hadrosaur bite is on top of the hip of a dinosaur that was about 18 feet (5.5 m) long and would have stood about 8 feet (2.5 m) tall. The only large predator that could have made a kill like that was T. rex. It is unlikely that any dinosaur would have been sitting still to allow a slow-moving T. rex to come over and bite it. In this case, it appears that T. rex would have been chasing the poor duckbill and bit down on it from above; certainly not something a scavenger would have done. It has been estimated that the bite of a large T. rex would have ripped as much as 500 pounds (225 kilos) of flesh and bone from its unfortunate prey.

Did T. rex ever scavenge for its food? The answer is that it definitely did – all top predators, such as lions and tigers, will eat something that is already dead. One theory put forward about T. rex is that as it got really big and heavy, it would have been able to scavenge more. Its huge size and ferociousness would have enabled it to chase off other predators who had made a kill and take it for itself. This had the advantage of T. rex not needing to expend the energy of chasing down prey, as moving five tons of dinosaur during a chase would have used up a lot of its energy reserves. Another fact that supports this idea is that a younger T. rex was proportionally lighter, and therefore faster and more agile. It wasn’t until they got up over 30 feet (10 m) long that they began to get really bulky and heavy.

Dr. Thomas Holtz, co-author of the Jurassic Park Institute Dinosaur Field Guide, has done a great deal of research on T. rex. He has looked at all of the evidence that has been presented by both sides of the arguments. Dr. Holtz cautions against accepting any of the opinions or conclusions as absolute fact. “Tyrannosaurs as a group (of dinosaurs) have locomotion (fast movement) related adaptations; long legs, shock absorbing feet and very large hip muscles,” he said. “T. rex was a better and faster mover than any other large predatory dinosaur and better designed for speed than large living animals like elephants.” He agreed with the possibility that a 3,000 pound juvenile T. rex may have been considerably faster that a six ton adult. Dr. Holtz said that T. rex went through several growth stages and as it grew the proportions of its body changed. “A young T. rex has the same body type as an ostrich-like (ornithomimid) dinosaur, much more athletic than a full sized adult T. rex.,” he said. “A young T. rex may have been able to run flat out, where a large adult may have been unable to run at top speed.”

The disagreements about T. rex behavior will probably go on for some time. It is not likely that any evidence will be discovered that will answer all the questions and leave no room for further discussion. Without a time machine that would give us a look at a living T. rex, we must continue to look at fossil evidence, however sparse and uncertain it may be.

Originally published as T. rex: What was it really? in 2002